Session

Intervention and embeddedness, art practice and environmental discourse

The use of art as a component of geographic enquiry has increasingly gained currency to the extent that the studio as the accepted location for art production has become as questionable as the assumption that dataset is the sole source of truth in a topological enquiry.

We wish to explore the symbiosis between geographer and artist in an interdisciplinary mode of enquiry, exploring how each might be reciprocally nourish the other’s practice. The context for this is the realization that the visual arts have a great deal to offer as a component of scientific enquiry leading to tangible outcomes.

This may only be affected through a reconsideration of the status of artist and the purpose of artwork.

Presentation

Art by Stealth

In this paper, using case studies from my own experience in the field of flood risk management, I will explore ways in which an artist can contribute credibly to public policy development. Art by stealth represents an acceptance of the difference between an artist’s intention and how it is construed. Working in partnership in a public arena often means that the autonomy of the artwork may not be as relevant as the primary need to clarify its application. Sometimes it is wiser to keep quiet about personal drivers for ideas and accept that if circumstances allow a project to happen, it might be too much to expect it to resonate in the same way to all parties.

Art represents a range of strategies that, if applied to the public sector, can generate links that would not be available if approached by any other means. Flood Risk Management is a stark discipline that implies a problem-solving methodology, which can founder at the consultation stage when community interests must be taken into account and process alone cannot address deeply seated issues of cultural memory. Because of its inherent freedoms, art is frequently given the role of least credible partner, which in a scientific context is at best to interpretative or a means for raising the visibility of a far more exacting discourse.

For every artist’s practice the intention that guides the process is fundamental to its application. In the realm of environmental debate, the strategy for me is that the making process is a necessary act of deliberation where, the principle of the integrity of the art object, in order to be effective, must be subsumed in the wider decision-making, problem-solving process.

About ten years ago I resolved that I should contribute as an artist more effectively to the environmental debate. Having already acquired insight into the workings of environmental legislation through earlier commissioning and consultancy work, now through my way of life on the Deben Estuary in East Anglia, I am able to add an understanding of the dynamic of coastal and estuarine systems.

From the beginning I understood the importance of grounding my research in an identifiable landscape and working directly in a pragmatic relationship with public organisations and the scientific establishment.

From the beginning I understood the importance of grounding my research in an identifiable landscape and working directly in a pragmatic relationship with public organisations and the scientific establishment.

To make this more straightforward I realised that I should revise how I position myself as an artist. The priority is that the discussion should happen and that I should have a place in it; I think I have been an artist long enough to have established a standpoint in relation to my own experience and this is unlikely to evaporate if for once it is not a dominant factor.

I realise that there are times when it is best to keep my motives to myself,

I realise that there are times when it is best to keep my motives to myself,

particularly when representing public interests in the debate over flood risk management. Being a member of far too many committees, I find that keeping up to speed with local debate parallels the need to keep abreast with developments in my own professional world, but I can still experience a sense of disconnection from my fellow committee members because my vantage point cannot be other than informed by questions of culture and the conundrum of what it is that binds people to place.

This is inevitable but not necessarily a problem. Together our deliberations are normally dictated by the need to extract certainty from a plethora of diverse and conflicting data; but curiosity and a belief in the importance of a holistic understanding drives me to immerse myself in it. In any coastal process and the change it precipitates, be it erosion, beach loss or flooding; technical research backed up by cost benefit analysis will render a range of solutions which, although utterly plausible will almost certainly not be acceptable at a local level where different imperatives apply that are determined by another agenda.

Consider the statutory demand to safeguard natural habitat in relation to the preoccupations of a farming community and it is easy to imagine conflicts of interest that, if unacknowledged can easily descend into acrimony. In any programme of environmental management, as the range of interests increases a single acceptable solution is less and less likely to be arrived at. Complexity is a precondition to establishing workable plans and for this to happen, it is no longer credible to think in terms of problems and their solutions.

Consider the statutory demand to safeguard natural habitat in relation to the preoccupations of a farming community and it is easy to imagine conflicts of interest that, if unacknowledged can easily descend into acrimony. In any programme of environmental management, as the range of interests increases a single acceptable solution is less and less likely to be arrived at. Complexity is a precondition to establishing workable plans and for this to happen, it is no longer credible to think in terms of problems and their solutions.

Alternative strategies must be explored. Although the conventional wisdom for an artist is to develop an identifiable practice with autonomous artwork as the goal, it would be counterproductive for me to subscribe to this as a modus operandi; my position is implicit in my approach; it is not necessary to state it because it is no more important than another point of view in the mix that might ensure an equitable solution. I am now more driven by what interests me than by carving out aesthetic territory.

Although I acknowledge the singularity of the work I produce and the structural solutions I develop, if dwelt upon, the idea of uniqueness could turn into an obstacle in the process of sharing ideas.

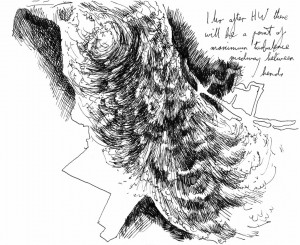

My involvement in this arena has not been undertaken without some soul searching; hubris always lies in wait for the unwary. Why should I expect a wilfully marginal point of view to influence a debate where other rules apply? However, encapsulated in it is the germ of another approach: sitting with a question, examining it in time and space, exploring aspects that may not be connected in a linear way: these are luxuries that are routine for me. Becoming grounded in the data that govern an investigation is vital, not as a precondition for finding a solution but to understand the condition of the enquiry.

It is instinctual, when confronted with a complex issue, that I should seek to find a way of getting it down on a single sheet of paper, to subject all the data to an homogenising process that allows the main issues to drift to the surface like the skin on a cup of coffee. This “sitting with” is an important lesson learned from studio experience, where a work through time suggests its own resolution. Should I fail to give myself the opportunity to sit with and absorb the essential characteristics of a project, I cannot feel justified in hazarding an opinion. Once I have identified an approach, it has a distinctive taste or texture that is only likely to shift if the parameters change.

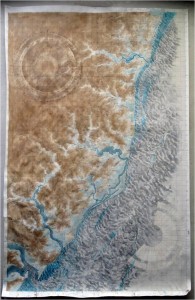

Aside from the more prosaic committee duties, I have developed two specific strands of enquiry. One is to re‐examine stated flood risk management policy through a series of mapping exercises. These aim to factor in all of the appropriate data known at a particular point in time in order to reflect in a wider

Aside from the more prosaic committee duties, I have developed two specific strands of enquiry. One is to re‐examine stated flood risk management policy through a series of mapping exercises. These aim to factor in all of the appropriate data known at a particular point in time in order to reflect in a wider

context upon the implications of change in a coastal and estuarine environment. Collectively I call this series of maps “Imagining Change”. The original trigger for them was the imminent need to respond to government coastal strategy documents in an informed way, demanding a high level of public comprehension. These works afford an opportunity to step back from a viewpoint that might be obscured by its own interests and to reflect. For example I took one strategy: the Suffolk Shoreline Management Plan, drew the entire coast where previously it was broken down to sectors, added the bathymetry, factored in the proposed options, conjoured up a NE storm on a rising tide and speculated. The freedom to speculate in this context is not an indulgence; it is essential.

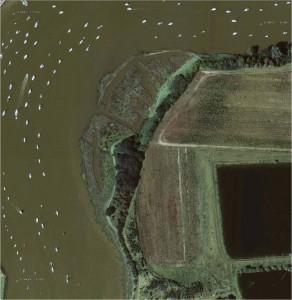

The other strand, which is closely related but not so instinctual, is to develop practical projects that can be accomplished at a community level with minimal resources, where, through direct action, the aim is to foster a sense of community ownership and awareness of coastal and estuary dynamics. So far these projects have sprung from the perceived threat to saltmarsh habitat on our river. We are blessed with a very large amount of saltmarsh, but all of it is deteriorating. The reasons for this are manifold, but still there is a perceived deficit, prompting the observation from “Natural England”, the UK Government Agency responsible for advising on the natural environment; that in order to secure the amount of healthy saltmarsh necessary to sustain bird populations it will be incumbent upon all coastal regions to augment their stock through a strategy of managed realignment. In this case the term “managed realignment” refers to breaching the floodwalls protecting farmland lying at or below mean high water.

The other strand, which is closely related but not so instinctual, is to develop practical projects that can be accomplished at a community level with minimal resources, where, through direct action, the aim is to foster a sense of community ownership and awareness of coastal and estuary dynamics. So far these projects have sprung from the perceived threat to saltmarsh habitat on our river. We are blessed with a very large amount of saltmarsh, but all of it is deteriorating. The reasons for this are manifold, but still there is a perceived deficit, prompting the observation from “Natural England”, the UK Government Agency responsible for advising on the natural environment; that in order to secure the amount of healthy saltmarsh necessary to sustain bird populations it will be incumbent upon all coastal regions to augment their stock through a strategy of managed realignment. In this case the term “managed realignment” refers to breaching the floodwalls protecting farmland lying at or below mean high water.

As can be imagined, for our relatively small rural river this is not a popular proposal, especially when applied to areas of land that have been reclaimed and managed for up to a millennium. If defences were allowed to fail, the effect upon tidal range and velocity would be detrimental to both flood risk management through the rest of the estuary and to navigation.

As can be imagined, for our relatively small rural river this is not a popular proposal, especially when applied to areas of land that have been reclaimed and managed for up to a millennium. If defences were allowed to fail, the effect upon tidal range and velocity would be detrimental to both flood risk management through the rest of the estuary and to navigation.

Under the present circumstances of extreme scarcity of funding for coastal flood defence, it has become clear that farmland, no matter how productive, will never achieve priority for protection, which can be interpreted as a gift to the salt habitat problem. However there is another argument: much of the reclaimed farmland is very old, in most cases its level is lower than the fringing saltmarshes on the seaward side of the defences, because the land has shrunk and dropped through centuries of drainage. On the other side of the wall the remaining saltmarsh has continued to accumulate sediment to the extent that there can be as much as 1.5 metre difference in level between outside and inside.

This means that any attempt to generate new marsh will not be possible without an intensive management regime, including recharging the area with dredged sediments. This is an option but not a cheap one. In response to this, our proposal has been to explore ways in which degraded saltmarsh might be restored and managed as a short to medium term measure whilst we ascertain more clearly the drivers behind its deterioration. In doing this, we have found that after some early robust opposition from Government agencies, we now have the fullest support in what is fast becoming an estuary‐wide project to look at saltmarsh under pressure and develop schemes on a case by case basis to encourage stabilisation and re‐vegetation.

We are now exploring a third project: a substantial area of fringing saltmarsh very close to the entrance to our river.

[nggallery id=18]

This has deteriorated due to the adverse effect of a recently installed pumped land drain system to replace a sluice that no longer had sufficient difference in level to function by gravity alone.

Add to this the incremental enlargement of drainage channels within the marsh and now the tide flows dynamically through the site on every tide washing out more sediment than it deposits. My initial approach has been to map the site and apply all the data that I can lay my hands on in order to acquire as thorough a picture as I can of what the influences for change might be. Only then will it be possible to decide whether it is feasible to intervene in a low‐key way to reverse the trend. With the resources of the Government Agencies behind us, we have access to a very wide range of data, including “LIDAR” surveys of the area, tidal flow charts and a condition survey conducted by Natural England.

[nggallery id=19]

If I can factor this wealth of information into a drawing/mapping exercise I stand a greater chance of familiarising myself with the main drivers for change within the site and that if a management plan is possible, I can approach it with a degree of conviction.

In the world constrained by markets, commodities, galleries and museums, authorship is provenance and therefore value; any ambiguity over this casts doubt over the status of an artwork. We all seek a milieu that we are comfortable with; it is a depressing fact that the orthodox machinery for the dissemination of art is not conducive to the kind of operation that I seem to be developing.

For these reasons I realise that in order to have an impact in areas I believe to be of utmost importance, I must develop an alternative strategy. It is a comfort to know that there have always been artists who aim to carry out a sense of societal duty through their practice, but realising this as an aspiration whilst retaining the integrity of approach can be elusive.

To me they must be made to harmonise or else any initiative risks being diluted to insignificance.